By Dennis Nealon

For decades, it’s been an academic showpiece—a storied institution for some of Boston’s brightest students. But today, the John D. O’Bryant School of Mathematics and Science in Roxbury is showing its age, a tired and dated star in the City’s public education ecosystem.

The good news is that City officials and building experts charting the future of the facility have been joined by laser-focused teams of Wentworth architecture students and faculty members. The students have proposed dramatic alterations to transform underused and inhospitable areas of the property’s three buildings. To counter the school’s institutional character, they’ve proposed letting the light in and bathing interiors in bright colors, creating a welcoming entrance, connecting buildings, conceiving spaces for school and community members to gather, bolstering security, adding sorely needed classrooms, and reconfiguring shadowy corners and passageways.

The plans emerged after an initial visit to the school last September, where the Wentworth cohort identified a series of issues, according to Boston architect and Wentworth Professor Mark Pasnik. “The interiors lack light and identity and do not effectively support the educational potential of the students who attend the school,” he said. “The most common descriptor we heard in interviews with more than 30 students was ‘prison.’”

Working across two semesters, the Wentworth student teams comprised fourth-year undergraduates from the Architecture program, led by Pasnik and two adjunct faculty members, architects Maressa Perreault and Aaron Weinert.

Boston Public Schools administrators, teachers and O’Bryant students have offered input.

“The architecture students took the information from our students and their own observations of the school to create great designs,” said Axel Martinez, a physics and engineering teacher at O’Bryant. He characterized the Wentworth contributions as key to the conversation about future revitalization.

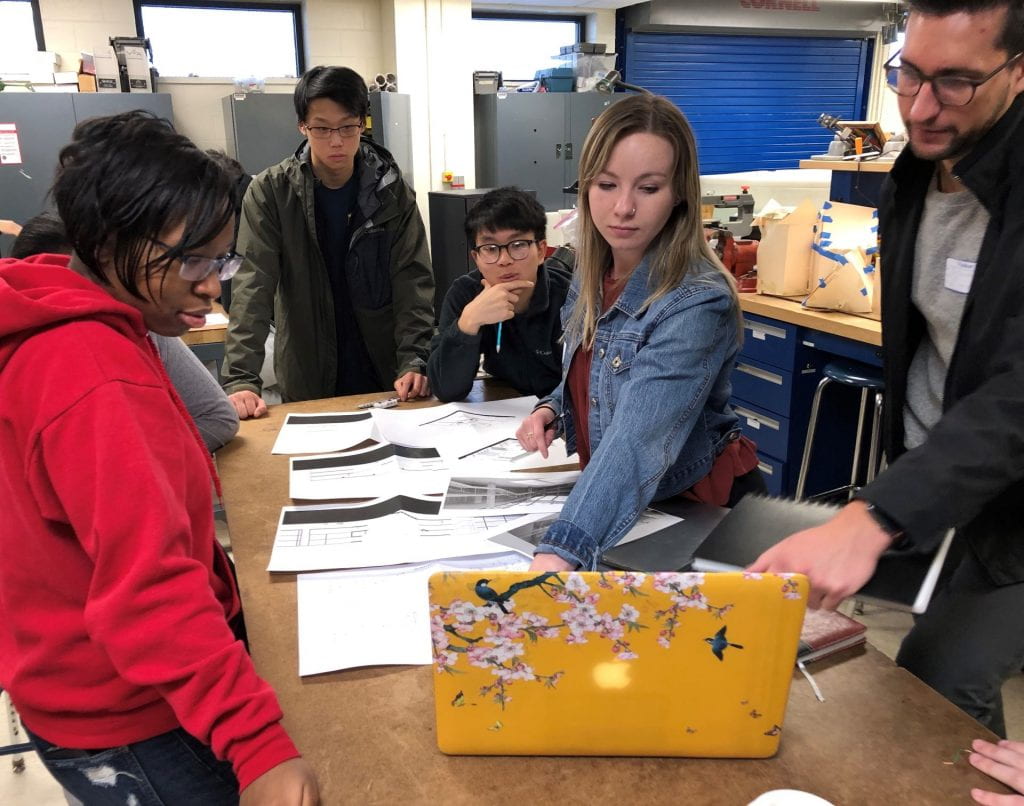

Wentworth students Angela Grant and Daniel Deodato (seen right) discuss ideas with Boston students (Photo by Mark Pasnik)

Referencing the BuildBPS facilities master plan, the students initially conducted a nine-point review of the complex with Patreka Wood, assistant headmaster, and interviewed nearly 40 juniors and seniors at the school. Early on, four potential improvement themes emerged, including developing an ecologically sustainable campus.

The O’Bryant School project reflects an eagerness on the part of City leaders to tap Wentworth for students’ imaginative fieldwork and the university’s faculty for their skills and familiarity with Boston. The consensus among officials, from City Hall to BPS to the State House, is that these kinds of collaborations make Wentworth a go-to place in a region full of renowned colleges and universities. Like

many Wentworth projects, this one is classically symbiotic. The City gets Wentworth’s young minds and academic expertise. The Institute uses Boston as a real-world classroom, providing students the practical, career-oriented education that is the soul of Wentworth’s academic model. The students rave about how much they’re taking from the process.

“Most of architecture is based on conceptual design,” said Leah Rogoz, a Spring 2020 graduate of the Architecture Program and an O’Bryant project team member across two semesters. “But reimagining a place that is already there has helped me visualize my ideas more than ever before.” She said her discussions with teachers, students, school employees and working professionals have given her “real-world experience outside of my major.”

Rogoz, who has a minor in Construction Management, plans to attend Wentworth’s Master of Architecture degree program in the fall, as does project team member Angela Grant, a spring 2020 graduate of the Architecture Program who called her own O’Bryant experience “fantastic” and “invaluable.”

The students’ work on the O’Bryant school continued virtually amid the COVID-19 pandemic. Final design reviews were conducted remotely on April 9, with teams unveiling ideas and presenting to critics, who offered suggestions and lauded the students’ work as being imaginative and aesthetically rich. BPS High School Superintendent Elia Bruggeman joined the final reviews both semesters and enthusiastically endorsed the students’ ideas.

Students Molly Aldrich and Allison West during their WIT Fall Studio Final Review with Boston Public Schools Superintendent Elia Bruggeman; Boston Public Schools Superintendent Lindsa McIntyre; Adjunct Professor Maressa Perreault; and Seunghae Lee, chair of the Department of Interior Design (Photo by Sam Rosenholtz)

Last December, some of the Wentworth students also previewed their work for Alexandra Valdez, director of engagement for the City’s Economic Mobility Lab; Lindsa McIntyre, BPS high school superintendent; Brett Dickens, assistant principal, Madison Park; Martinez; and two O’Bryant students.

More than 12 project critics, including architects Kelly Haigh of DesignLab and Tricia Kendall of Tricia Kendall Architecture & Design, reviewed the students’ concepts and designs. For the remote-learning format in April, Bruggeman, Valdez, Martinez, Haigh and Kendall returned with several other critics and school officials to offer insights that built on earlier findings.

Pasnik said a report on the O’Bryant revitalization will be developed over the summer, with expected completion in September. The document will be shared with leadership from the school, BPS and the Mayor’s Office, and will be broadly accessible online.

In the fall, Pasnik and a new group of students and faculty will be turning to the adjacent Madison Park Technical Vocational High School abutting the O’Bryant property.

“This has been an extraordinary experience for our students,” said Pasnik. “It’s precisely what we mean when we talk about the opportunities Wentworth provides to engage the world around us in a meaningful way.”

1 Comment

As a Class of 1956 Wentworth graduate of the Architectural Construction course, the first class to receive a WI associates degree, I am extremely proud of the development of my alma mater and of the work they are accomplishing for the benefit of Roxbury’s young students.